A further article was written by Lynda Nicol and published in the East Kilbride News on 24th March 2004. I received kind permission from Lynda to reproduce her article and you will find it at the bottom of this page.

Article written by Bill Niven as part of the Local History Corner

Robert Fergus Smith was born on January 15, 1918.

Fergie, as he was always known, came with his parents and elder brother Graham to what was then Maxwellton Road, East Kilbride, in 1919.

In November of each year, we celebrate and honour the fallen of both World Wars and I have published articles in the East Kilbride News on the East Kilbride War Memorial in Graham Avenue where the sacrifice of the 105 men and women, who gave their lives in the pursuit of freedom, are commemorated.

On this occasion I feel it would be appropriate to record the war experiences between 1939 and 1945 of Fergie Smith as representing all those whose courage and valour through torment and hardship overcame the threat of Nazi aggression.

The Outbreak of War - 1939

Fergie Smith was 21 years old when World War II broke out on September 3, 1939. After the invasion of Poland by Germany on September 1, war was declared by Britain and France two days later.

Football and golf were Fergie's two main sporting interests. I have in front of me his 1939-40 membership card of East Kilbride YMCA Football and Athletic Club. There are some well-kent names among the office bearers - Chris Thomson, John Cadzow, Bill Ainslie, Douglas Smith and Quintin Watt. Fergie had joined East Kilbride Golf Club as a boy of eight and over his life was to retain membership for more than three-quarters of a century. In both games he excelled, playing as a half back with the YM football team and a long standing team player with the golf club.

On December 15, 1939, Fergie enlisted in the Royal Engineers as a motor driver. His soldier's service book gives his weight as 11 stones. By the end of the war, however, his weight had plummeted to six stones. His daily rate of pay was two shillings (10p). He was 5 feet 7 1/2 inches tall and his general physical and mental health was recorded as A1. He was to need all his strength and determination to survive the six years ahead of him.

Capture at Boulogne - May 21, 1940

Fergie was posted to Anglesey in Wales to start a comprehensive training course which lasted for 90 days.

His training involved gunnery, use of mines and driving techniques. He was part of the Second Militia, Royal Engineers and his squad of sixty were shipped to France on April 28, 1940. The ship arrived at Le Havre and hundreds of troops were waiting to return to the UK. Fergie could not understand why they were off-loaded and sent to the frontline to hold up the rapid advance of the German army. Thousands were killed or wounded in the retreat and Fergie's unit arrived in Boulogne on May 20. Fergie and his comrades took shelter in coal cellars under the houses. A French spy gave their position away, the doors were opened and an armed German officer forced the British soldiers to line up against the wall. Two German machine gunners lay on the road waiting for the command to shoot. The German captain told them they would be transported to Germany. They began a long trek of 300 miles to Luxembourg where they boarded a cattle truck for three days before arriving at Stalag XXA near Torun in Poland. This was the beginning of five years in captivity after but 22 days in France.

It is sobering to think that these same cattle trucks were used from 1942 to transport Jews and other minorities to the gas chambers.

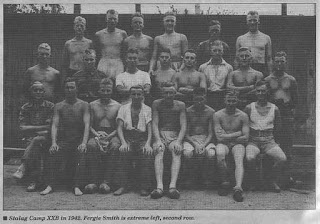

Stalag XXA - 1940-1941

On arrival at Stalag XXA, photographs were taken and metal discs given to each of the prisoners to wear around their necks at all times. Fergie's was number 6383. Roll call was taken every morning at 6 am, taking up to three hours to count the 10,000 men. Breakfast was a bowl of watery cabbage soup. In due course, working parties were transported to various towns and villages. Fergie's squad spent the winter levelling the ground for houses to be built for the German families who were to occupy Poland. One hundred men slept in a wooden hut 18 feet by 15 feet. There were four rooms , each with a stove in the middle. The prisoners found these conditions much improved from the main camp. The POWs left at 6 am each morning, marched for two hours, worked until 5 pm and then arrived back at the barracks at 6 pm for a bowl of soup and two slices of bread. This diet undermined their strength and a number of POWs were lost through dysentery and diptheria. The winter of 1940 was bitter and the soldiers slept fully clothed, including balaclavas. Some Red Cross parcels were now arriving at Stalag XXA. A parcel for Fergie contained, among other things, two shirts, one pair of gloves, one foot bruch, razor blades and soap, two pullovers, 12 cakes of chocolate and two pencils.

Stalag XXB - 1941-1945

In March 1941, Fergie Smith was transferred to a new camp Stalag XXB at Marienburg on the Baltic Coast. His squad worked at a sawmill at Elbing near Danzig (now Gdansk). The barracks had improved and conditions were better, with a British Medical Orderly and medicines available. However, in June 1941, Germany invaded Russia and the prisoners could observe the troop trains moving to the frontline for months on end. Towards the end of 1941, life improved further with regular deliveries of Red Cross food and clothing parcels. The POWs were now allowed to send one postcard with six lines ( passed by censor). There was also a well-organised round of sporting activities in the area. The prisoners' newspaper The Camp carried a report of the Elbing District Sports in its issue of July 18, 1943. The final of the District League was fought between the Whites and the Yellows. Fergie Smith was captain of the Yellows and was reported as "having played a great game". Fergie also distinguished himself in the Inter District Sports as a member of the winning 800 metres relay team. In early 1945, when Russians made their major push towards Germany through Poland, the German High Command ordered all 10 camps in the area to be brought back to safety into Germany. The 1000 prisoners awaited transport, but none was available due to the Russian advance. As Fergie wrote: "Thus we were put on a death march, which lasted nine weeks and covered 1000 miles before being liberated near Hamburg."

"My story of the march, day by day, can be read in my diary." (The picture to the left is of Fergie at the end of the war in 1945).

The winter conditions made survival at night a major problem. A significant number of prisoners died of exposure and Fergie's answer to the dangers of sleeping on the ground, was a piece of rope with which he attached himself to a tree in order to prop himself up while sleeping. The columns were stationed at Hitzacher for almost two weeks and during the day were transported to neighbouring villages on work parties. On April 14, he noted the death of President Roosevelt and on the 18th the meal was peas, margarine and bread.

On Tuesday, April 24, tragedy struck - the column was travelling through Putlitz when a German vehicle came thundering up from behind. As it passed, Fergie realised that a Nazi officer was preparing to shoot and in the next 60 seconds three soldiers were dead and another fatally wounded.

The four men were:

Jim Clarkin, Black Watch of East Kilbride

Ronald Jackson, Green Howards

Gordon Pollitt, Kings Regiment

Albert True, Queen's Own, West Kent

Fergie described this day as Black Tuesday in his diary. The four men were buried two days later. With heavy hearts, the survivors reached Luneburg on May 2 and witnessed an historic moment in history.

General Bernard Montgomery came across to speak to them:

"You will be happy to know boys that I am about to sign the peace pact."

The Diary of the Death March

Fergie's diary comprises a slim 80 page notebook measuring four inches by 2 1/2 inches. The brown cardboard covers are now faded but the Teutonic scrolling and geometic designson the front cover are clearly visible. The quality of the lined paper is good and the diary was probably bought in Stalag XXB in 1942.

The account of the Death March comprises 10 pages in the centre of the volume. After Fergie's personal details at the beginning, there are the names and addresses of some two dozen of his comrades during his internment.

At the rear of the diary is a list of letters sent and received during 1942 and 1943. There was correspondence with his mother and father, brother Graham, Aunt Maggie and Uncle John. Outside the family circle were the Rev. Walter Millar, Mary Kirkwood, neighbours the McCormicks and the McNicols, John Templeton and his golfing buddy Bobby Graham.

The diary of the journey is headed The Great March back from Dirschau, West Prussia, which began on February 20, 1945, and ended at 10.45 am on Wednesday, May 2, 1945, when the marchers were liberated by the American troops.

The narrative is written in pencil and gives a faithful account of the daily journey in kilometres and the itinerary followed.

There are cryptic notes:-

February 25: Red X parcel (12 men)

March 6: Here we lost the column for 2 days

March 12: Rest day at Neuenkirchen

March 26: Brilliant day by RAF!

April 1: Sunday holiday - Easter Sunday

Postscript

Fergie Smith was repatriated to a hospital in Surrey where he recovered from a debilitating illness and from there transferred to Hairmyres Hospital. Sadly, Fergie's father Sam died on the very day of his son's liberation.

Now it was back to life as a civilian working for Philips of Hamilton. Marriage to Norma (left with Fergie) followed in 1949 and daughters Pamela and Linda arrived in due course.

Fergie Smith resumed his place in the YM football team and became club champion at East Kilbride Golf Club in 1953. With Norma, he won the family foursomes for a record three times.

His later years were hampered by indifferent health and the death of his wife Norma in 1999 was a major blow to him.

I am much indebted to his daughter Pamela for the memorabilia from which the narrative is drawn. As I studied the mass of documents, letters, photographs and newspaper cuttings, I became acutely aware of the horrors of war and its aftermath of personal tragedy. I knew and respected Fergie Smith for more than half a century and will longer remember his charm and bonhomie. His passing on May 17, 2002, leaves all who knew him with a deep sense of personal loss.

Fergie's wartime experiences and his valour and grit were shared by many others during hostilities. His story, however, is his alone and is without dout that of a very brave man indeed.

Editor's note

The sheer scale of war can often mask the horror of it all. Read that so many hundreds perished here or so many thousands died there and the senses are almost switched off, numbed by the terrible truth behind the cold weight of facts and figures. Yet when we read about one man's struggle to survive against all odds, the hellish reality bites home with a vengeance, leaving the reader deeply moved. Leafing through Fergie's diary, it becomes apparent that there is not one hint of self-pity in the face of adversity or self-praise following the daily act of heroism that was simply staying alive on the Death March. His story reminds us once again that many from the wartime generations had - or maybe they developed - special qualities that we who live in different times may never possess. It further reminds us that we are indebted to those who put their lives on the line so that we can live today as free men and women.

Gordon Bury

All information on this page is © of the East Kilbride News and should not be reproduced in any way without the express permission of the Editor.

War prisoner's tale is still a top read by Lynda Nicol

An article about a local man who spent five years as a prisoner of war in the infamous Stalag camps is still being widely read by people all over ther world 16 months after it was first published in the East Kilbride News.For the article about the late Fergie Smith by local historian Bill Niven has been printed in full on a website which specialises in World War II memories with the permission of the News and its author.

The article has aroused considerable interest and inquiries from the families of men whose circumstances were similar to those of Fergie.

Bill told the News that the website will also be of interest to many readers.

Fergie Smith, whose family moved to East Kilbride in 1919 when he was just a baby, enlisted in the Royal Engineers on December 15, 1939 shortly after the outbreak of the war.

After training his squad was shipped to France on April 28, 1940.

Fergie and his comrades were captured by the Germans in Boulogne on May 20.

In his diary, Fergie told of the long 300 mile trek to Luxembourg to board a cattle truck to take them to Stalag XXA near Torun in Poland.

This was the beginning of five years in captivity after just 22 days in France.

Roll call was taken every morning at 6am and breakfast was a bowl of watery cabbage soup.

In due course, working parties were transported to various towns and villages. Dinner was also a bowl of soup and two slices of bread.

This diet undermined their strength and a number of POWs were lost through dysentry and diptheria.

In March 1941, Fergie was transferred to a new camp Stalag XXB at Marienburg on the Baltic Coast where his squad worked at a sawmill at Elbing near Danzig (now Gdansk).

But in 1945, when the Russians made their major push towards Germany through Poland, the German High Command ordered the prisoners brought back to Germany.

There was no transport and, as Fergie wrote: "Thus we were put on a death march, which lasted nine weeks and covered 1000 miles before being liberated near Hamburg."

SURVIVAL

The winter conditions made survival at night a major problem. A significant number of prisoners died of exposure before the marchers were liberated by American troops on May 2, 1945.

Fergie Smith was repatriated to a hospital in Surrey and later transferred to Hairmyres Hospital.

Fergie Smith resumed his place in the EKYM football team and became club champion at East Kilbride Golf Club in 1953. With Norma, he won the family foursomes for a record three times.

His later years were hampered by indifferent healt and the death of his wife Norma in 1999 was a major blow to him. Fergie died in May 2002.

To read his fascinating story in full, as it appeared in the News in 2002, go to WWII Memories.

August 2017: Keir contacted me to say "My name is Keir Tetley and I am the Great-Grandson of Gordon Pollitt (King's Regiment), who is noted in the story of Robert Fergus Smith as having being gunned down by a German officer in a vehicle on the 24th of April 1945.

Two or Three years ago we visited Gordon's grave in Putlitz. He is still there along with the graves of Ali Gasam, James Clarkin, Ronald Jackson, Sugk Kisan and Albert True. I believe Ali was also killed at the same time as the four mentioned in the account of Robert Smith. We surprised the groundskeeper who was very emotional at the fact a family had arrived to see the graves of the Commonwealth soldier he tended to."

No comments:

Post a Comment